Seed |

|

|

Bunya | Brachychiton | Santalum | Sterculia |Tasmannia spp |

|

Acacia spp. (Wattle) |

|

Acacia Sophorae |

|

Coastal Wattle |

|

Acacia aneura |

|

| Mulga |

|

|

|

|

Acacia murrayana |

|

Colony Wattle |

|

|

|

|

Acacia victoriae |

|

Elegant Wattle |

|

|

|

|

Acacia longifolia |

|

Sydney Golden Wattle |

|

|

Family: |

Mimosaceae |

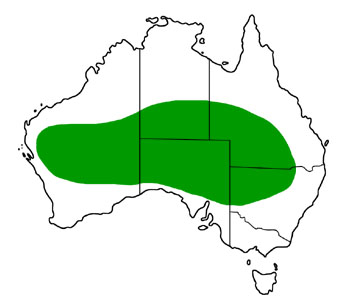

Acacia sppParticularly: Acacia aneura - Mulga; Acacia longifolia, variety sophorae - Coast wattle; Acacia murryana - Colony wattle; Acacia retinodes - Swamp wattle, Wirilda; Acacia victoriae - Gundabluey, Bramble wattle. WattlePlease note: It was impossible to cover all the edible wattles and thus I have chosen species suitable for coastal/rainforest (A. longifolia variety sophorea), arid zones (A. murryana, A. aneura and A. victoriae) and temperate (A. retinodes). See new addition - Acacia colei. General notes:The seeds of many wattles are edible. However - please do not assume that an unidentified wattle seed is safe to eat. Also note - if you are considering introducing an Acacia from outside your area, please check that it is not prone to becoming a weed species. The overall nutritional value of Acacia seed is fair to good, similar to other legume seeds but with a higher level of dietary fibre. 58 samples tested by CSIRO 1 yielded 23% crude protein, 26% available carbohydrate and 32% fibre. Most Acacia species are relatively short lived. Many Acacias have multiple uses: A. sophorae - sand binder, wind break A. retinodes: wind break, timber, fodder, land reclamation A. victoriae - fodder Edible portion:Seed/seed pod Harvest period:A. aneura - late spring or other times, depending on rain. A. sophorae - summer A. murryana - summer A. retinodes - late summer to autumn A. victoriae - summer Yrs to maturity:Wide variation - almost all wattles are reasonably fast growing. A. aneura is probably the slowest growing of the species listed, A. murryana, A. retinodes and A. victoriae possibly the fastest - 2-3 years. Form:A. aneura - small tree or large shrub to 7 m high by 7 m across, often multi-stemmed. A. sophorae - small tree, 4-5m or med shrub 1-5m A. murryana - multi stemmed shrub or small tree, 5-8m. A. retinodes - multi stemmed shrub 3-8m A. victoriae - small, straggly multi stemmed small tree 2-5m. Seed size:A. aneura - medium A. sophorae - medium A. murryana - moderately large (18000-27000 viable seed per kg) A. retinodes - medium A. victoriae - round, moderately large - approx 24,000 seeds to the kg Natural Distribution/Growing conditions:A. aneura - widespread in arid inland in SA, NSW, QLD, WA and NT A. sophorae - restricted to coastal regions SA, Tas, Vic, NSW, Qld - forms dense, low thickets behind beaches. A. murryana - widely distributed in arid and semi arid zones of Qld, NSW, SA, NT and WA. Found in deep sands but will also grow in well drained clay loam. Relatively salt sensitive. Does not tolerate water logged sites. A. retinodes - SA, southwest Vic and Tas. Will take coast exposure, saline and lime conditions. Will also tolerate heavy, waterlogged soils. A. victoriae - widely distributed in all states but Tas. Mainly in woodlands, grasslands and along waterways. Found on a large range of soils from clay to loamy sands. Tolerates saline soils, draught and brief periods of waterlogging. Climatic conditions:A. aneura - low rainfall areas (200mm-400mm). A.sophorae - medium rainfall A. murryana - low rainfall (100-500mm)) A. retinodes - temperate regions with moderate rainfall (400-1000mm). Reasonably frost tolerant A. victoriae - Temperate to subtropical areas of low rainfall (125 to 500mm) and hot inland conditions. Will tolerate heavy frost. Management reference:It is suggested that drip lines and slow release fertilisers will enhance development. The main pests are stem borers which can be controlled by probing with flexible wire or by injecting a few ml. of alcohol into the holes. Galls are often more difficult to control, but removing the effected branches can reduce the problem. Acacia bug (Eucerocoris tumidiceps) can cause damage to the foliage of wattles with phyllodes and is difficult to control. A. aneura - full sun and good drainage essential. Will tolerate frosts to -7o C ). A. retinodes - suitable for dryland plantings. A. sophorae - light soil, good sun. Not so frost tolerant when young. A. murryana - an adaptable species. Coppices well. Suckering habit - has potential to become a weed species if introduced to disturbed areas. A. retinodes - prefers sunny moderately well watered position and is capable of very rapid growth in moist soils, even tolerating heavy, water logged conditions. Moderately frost, drought, lime and saline tolerant. Handful of organic fertiliser when planting and side dressings of fertiliser spring and autumn. A. victoriae - fast growth rate. Prefers sunny position will tolerate many soils and, once established will tolerate drought, frost, saline conditions and lime. Handful of organic fertiliser when planting and side dressings of fertiliser Spring and Autumn. Coppices well and is known to sucker. Early side pruning will make subsequent seed harvest easier. Density:3m x 3m to 5mx5m generally = 500 - 625/ha A. aneura - 3mx3m (625/ha) A. retinodes - 4m x 5m = approx 500/ha A. sophorae - 5mx5m = approx 350/ha A. victoriae - 4m x 4m - (500/ha) Yield at maturity:Generally - 1.5 kg/tree - quoted as 1.25 tonnes/ha A. victoriae: a high yielding species producing 6,000 seeds per kilogram and on average up to 10 kilograms of seed per tree. Traditional Aboriginal Use:Seeds/seed pods, ripe or green were roasted and eaten. Green seed pods steamed and eaten. Harvesting:Shake and collect or hand pick. Post harvest cleaning and handling is an area being researched at present. It is suggested that you find a seed processing firm for this stage! Supplied as:Whole raw seed, dried or dried and ground Typical value adding:Roasting and grinding. Roasting enhances their natural nutty, coffee-like flavour. The seed from A. victoriae has a deep, rich, almost chicory flavour, the southern coastal wattle has a larger, fattier seed with more nutty overtones. A fine flour is made by milling (preferably hammer). Wattleseed may be used as a crust for fillets of lamb or beef. It works extremely well in dairy based dishes such as creme anglais, brulees, ice creams and mousses. It will also add flavour to baked goods such as biscuits, butter cakes, breads, etc. If using in flour-based products, add the wattleseed at the end of the mixing process, as it can toughen the gluten content of the flour. Bring a small quantity of wattle to the boil to soften the grounds. Strain off the liquid extract and store in the refrigerator or freezer. Use the boiled grounds in marinades, as a crumb for meats or as a batter for fish. Use the extract with or without the solids to make wattle ice-cream, pavlova and wattle pancakes. Wattleccino (wattle cappuccino) is fast becoming famous. Only one teaspoon of wattle per cup is needed so it is very economical. Cherikoff and Brand have demonstrated that the seeds are high in protein (17% to 25%), fat (4% - 16%) and carbohydrates (30%-40%). CSIRO project are undertaking work on Acacias at present. Note: A. aneura and A. melanoxylon are also fine hardwood timbers suitable for agroforestry. Current purchasing price:Variable - quoted from $10.00 to $70/kg. The RIRDC quoted $30-$35/kg cleaned and roasted, $53-$59/kg cleaned, roasted and ground. Check out the Products page on the website: www,ausbushfoods.com Perceived demand:High. The bush food industry is anxious to secure readily available supplies of acacia seed. From the RIRDC Report

"Cultivation of Native Food Plants in Southeastern Australia" Acacia coleiDescription:A large quick growing shrub variable in size from 2 - 7 metres, it has smooth bark, cylindrical yellow flower spikes, silvery broadish large leaves with small seeds produced in long narrow pods. Ecology:Species not generally common and found north of Alice Springs. Uses:A good producer of seed that is easily harvested and used as with other acacias. Seed is eaten, grubs can be harvested from the plantís roots and honey dew (a sweet sugary sticky substance) produced by scale infestations makes for a great drink. Propagation Notes:As per most acacias the seeds are best soaked in previously boiled water for at least 12 hours or until the seed has swollen. Cultivation Notes:

As per most acacias they are quick growing and need minimal care once established. Controlled irrigation regimes will improve growth rates and maybe managed to improve flowering and yields as this tree particularly favours good conditions. Economic Opportunities:As per many acacias, however this acacia is considered by some to have more potential than Acacia victoriae, a species mostly sought after by the Australian bush food industries. (Morse, 2003) See also Acacia murrayana in the RIRDC report "Cultivation and Sustainable Wildharvest..." See also - Acacia. |

|

| TOP | |

Araucaria bidwillii |

|

Bunya bunya nut |

|

|

Family |

Araucariaceae |

General notes:Usually a scattered emergent in rainforests. Should not be planted where falling cones might cause damage or injury. Large starchy textured nuts within a tough, woody casing from the cone of the huge Bunya pine tree that is native to New South Wales and Queensland. These nuts are similar in size and flavour to chestnuts and make a delicious bunya nut puree. Each nut is encased in a thin woody shell which can be sliced with a knife after boiling the nuts and while they are still hot. The shelled nuts can then be blended to make a pastry, used as a potato substitute in curries and stews, minced for use in chocolates, nougat, ice-cream or other desserts and even preserved in sweetened rum. Edible portion:Nut Harvest period:Dec-Feb - has shown a 3 year cycle of 'bumper' crops Yrs to maturity:5-8 Form:Large tree - to 30m Natural Distribution/Growing conditions:Rainforests and open forest in coastal SE Qld inland as far as the Bunya Mountains. Also in a small 'pocket' in Northern Qld. Trees have been observed bearing well in dry areas of SA. Climatic/microclimatic conditions:Sub tropical to temperate. Favours sunny positions Management reference:Nil. Requires good deep soil for best development. Traditional Aboriginal Use:An important food, especially during the triennial Bunya feasts Density:Unknown - a large tree probably not suited to plantation . Yield at maturity:A good, mature tree, in the triennial harvest, can drop as many as 70-80 cones. Net kernel from each cone is around 1kg. Harvesting:Cones drop to the ground - removing nuts from the cone and the leathery outside coating, as well as the very tough shell, is still a time consuming process. Supplied as:Whole raw seed or roasted & ground or frozen. Typical value adding:De-shelled and vacuum packed, dried, pickled, flour. Current purchasing price:$1-$15 /kg (depending on whether it's been deshelled and processed) Perceived demand:Varies - there appears to be demand at present (2006) |

|

Brachychiton populneus |

|

Kurrajong, Illawarra flame tree |

|

|

Family |

Sterculeae |

General notes:A fairly common street or garden tree. Note - seed should not be eaten raw. There is a Brachychiton species in most areas of Australia and all have edible seeds. Edible portion:Seed Harvest period:Mar-May Yrs to maturity:2-3 Form:Tree, 8-20m. Natural Distribution/Growing conditions:Widespread in Vic, NSW and Qld Climatic/microclimatic conditions:Most readily in temperate 450-750mm rainfall areas but found in much higher rainfall, warmer areas. This species has been introduced to a wide variety of climatic habitats and appears to flourish in most. Management reference:Slow starter but grows more rapidly after year 2-3. Southern provenances frost tolerant. Traditional Aboriginal Use:Roasted Density:Approx 600/ha Yield at maturity:Unknown Harvesting:Hand. Care should be taken when harvesting as small, very irritating hairs line the pods and surround the seeds. It has been suggested that the pods can be opened and put in a cement mixer until the seeds fall out - a light braising will then rid the seeds of the remaining hairs. Supplied as:Raw seed (with hairs removed!), roasted or roasted and ground. Typical value adding:Should not be eaten raw. Light roasting and coarse grinding for addition to breads, pancakes etc. Can also be added to rice when cooking. Heavily roasted seeds were ground and used as a substitute for coffee. Current purchasing price:$ Unknown Research also:B. paradoxyum, B. acerifiolius Perceived demand:Medium at present - could be improved |

|

Brachychiton gregorii |

|

Desert Kurrajong |

|

|

Family |

Sterculeae |

Santalum spicatum |

|

Sandalwood |

|

|

Family: |

Santalaceae |

General NotesA species of sandalwood, is a tree native to semi-arid areas of southern and western Australia. Sandalwood is the source of sandalwood oil, a high value oil used in perfumes, soaps and incenses .It grows in the same habitat as a Quandong (Santalum acuminatum); both are semi-parasitic and have a similar habit. Edible PortionKernel Harvest PeriodJune-December Years to Maturity10? Form.Typically an erect small tree or shrub, 3-8 m tall and 0.1 -0.3 m diameter. The tree crown is greyish in appearance and rather umbrageous. The bark is rough, fibrous and furrowed on the lower parts of the tree but the upper limbs are grey or blue and smooth. Fruit is spherical, about 3 cm in diameter. Natural Distribution/Growing conditions:Sandalwood distribution is mainly in the warm semi-arid climatic zone having low rainfall for most of the year. The species occurs in a wide range of forest types from woodland to low open-woodlands. Climatic/microclimatic conditions:Altitude: 0-500 m Mean annual temperature: 18 deg C Mean annual rainfall: 150- 500 m Soil type: Sandalwood grows on a variety of soils from calcareous red earths to red earthy sands in Western Australia to solonized brown soils and shallow calcareous loamy soils in South Australia. These soils should however be well drained. Management reference:Sandalwood trees are a root parasite on many species. Some common recognized hosts are Eucalyptus salubris, Eucalyptus loxophleba, Casuarina cristata subsp. pauper, Acacia aneura, Atriplex vesicaria, Pittosporum phillyreoides, Acacia acuminata, Senna siamea and Pongamia pinnata. It has a spherical kernel which forms the bulk of the fruit. Very difficult to germinate, requiring warm, moist conditions not normally found in their natural habitat. In most years they would not naturally germinate. Possibly they depend on the el nino cycle. Success has been reported by placing the kernels in moist vermiculite in sealed plastic bags at room temperature. Once germinated, it should be planted next to a (preferably Australian native) seedling, and watered adequately. The sandalwood is a hermaphroditic species. Flowering is sporadic because of the irregular rainfall in most areas where S. spicatum grows. Flowers are carrion-scented and nectariferous, attracting a wide range of insect pollinators. Fruits ripen from June-December. Polyembryony is reported for the first time in S. spicatum (from western Australia). Results from preliminary investigations into genetic diversity within S. spicatum in western Australia indicate genetic distance between S. spicatum ecotypes increases linearly with geographic distance. Natural regeneration, seedlings and direct sowing are convenient modes of propagation of this hemi-parasitic species. An important characteristic of sandalwood is that it is a parasite that attaches to the root system of the host tree. Fortunately, the host range appears to be wide, offering the possibility of growing sandalwood in combination with horticultural tree crops, such as mango and cashews or tropical timber species, such as mahogany and teak. It is not known how long the sandalwood trees grown under irrigated plantation conditions will take to reach maturity, but it is expected to be at least 20 years. Though a light demanding species, the tree tolerates shade and soil salinity but is susceptible to frost, fire and grazing damage. Provided that areas can be protected from grazing, successful regeneration can be enhanced. The estimated maturation time for the sandalwood in Kalgoorlie District, Australia is 50- 100 years. Establishment of S. spicatum on an operational and plantation scale can be achieved by sowing 4 seeds per spot in well drained sites, 50-70 mm below the soil and mulching in a small depression at the drip line of the south side of a suitable host plant. Sandalwood is harvested by uprooting trees from the ground by means of horse, camel power or heavy-duty vehicle. In the past the bark and sapwood were removed by adze and discarded but at present only the bark and the sapwood is removed. The roots, stems and large branches are all utilized down to 2.5 cm diameter, dead sandalwood stems are also used. Results show that growing seedlings rely heavily on their mineral seed reserves for about a year. Seed reserves and root intake are not sufficient to reverse a decline in mineral concentration as the seedling develops its shoots and root systems. Haustorial connections must be made not later than the time of minimum concentration. Ammonium sulphate at 779 kg/ha (especially in combination with an Acacia host), sodium phosphate at 571 kg/ha or a combination of these fertilizers appeared promising treatments for young S. spicatum. 90 days of Osmocote (hoof and horn or blood and bone meal) application at 50 kg/ha was also beneficial but superphosphate was not. Osmocote can be regarded as the most beneficial fertilizer. Increase in root dry weight was greatest with its application. Increased Ca levels stimulate seedling growth, while lack of Ca and N is soon lethal. Uptake of Ca, N and Sodium obviously occurs via the plants' own root system, and any treatment which increases root growth may encourage early uptake of these limiting minerals. Germplasm Management Mechanical scarification improves germination. The seed germinates after extremes in temperature and rainfall. Field studies indicate that only 1-5% of S. spicatum seeds germinate. The rate of germination is higher in reserves and protected research and plantation areas, but is still less than 20%. S. spicatum seedlings tend to die if their roots fail to attach to suitable hosts. The deaths therefore may be due to the inability to obtain some type of element for which the host is essential or the inability to take up sufficient nutrients to maintain growth. Mixtures containing fertilizers exhibited increased height. The continued growth of the seedlings depends on attachment to a suitable host. Traditional Aboriginal Use:Kernels were eaten Density:? Yield at maturity:? Harvesting:Hand/Machine Supplied as:Raw nut. The kernels are very rich in a fixed oil (ca. 45-55%) and this oil is characterized by a high percentage of unusual acetylenic fatty acids. The seed cake contains approximately 50% crude protein and is potentially a nutritionally rich food item. Seed lipids contain about 49% oleic acid and about 40% ximenynic acid. The oil consists of three major triglycerides: triximenynoyl-glycerol (triximenynin), an oleoyl-diximenynoyl-glycerol, and a dioleoyl-ximenynoyl-glycerol. Essential oil: An aromatic oil can be distilled, mainly from the tree butts and roots, the oil is used as a fixative for perfumes and in high quality soaps. Steam distillation, yields 5 sesquiterpene alcohols, epi-alpha-bisabolol, (Z)-alpha-santalol, 2(E),6(E)-farnesol, (Z)-beta-santalol and (Z)-nuciferol. The percentage of epi-alpha-bisabolol increases with increasing height up the tree and even the volatile fraction of a dead branch contained. Two santalols,(Z)-beta-santalol and (Z)-nuciferol, were highest in the buttwood. Other products: The oils are incorporated into high quality soaps. Typical value adding:Unknown Current purchasing price:$ Perceived demand:BibliographyBarrett DR. 1987. Initial observations on flowering and fruiting in Santalum spicatum (R.Br.) A.DC. The Western Australian sandalwood. Mulga Research Centre Journal. 9: 33-37.Barrett-DR, Wijesuriya-SR and Fox JED. 1985. Observations on foliar nutrient content of sandalwood (Santalum spicatum R.Br. D.C.). Mulga Research Centre Journal. 8: 81-91. Boland DJ. et. al. 1985. Forest trees of Australia. CSIRO. Australia Brand JE. 1993. Preliminary observations on ecotypic variation in Santalum spicatum. Mulga Research Centre Journal. 11: 13-19. Crossland T. 1982. Response to fertiliser treatment by seedlings of sandalwood, Santalum spicatum (R.Br.) DC. Annual-Report, Mulga Research Centre, Australia. No. 5:13-16. Faridah Hanum I, van der Maesen LJG (eds.). 1997. Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 11. Auxillary Plants. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, the Netherlands. Fox JED and Brand JE. 1993. Preliminary observations on ecotypic variation in Santalum spicatum. 1. Phenotypic variation, Mulga Research Centre Journal. 11:1-12. Kulkarni HD and Srimathi RA. 1981. Polyembryony in the genus Santalum L. Indian Forester. 107 (11): 704-706. Liu Y et al. 1995. A comparison of kernel compositions of sandalwood (Santalum spicatum) seeds from different Western Australian locations. Mulga Research Centre Journal. 12: 15-21. Liu YD et al. 1997. Separation and identification of triximenynin from Santalum spicatum R. Br. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 74(10): 1269-1272. Loneragan OW. 1990. Historical review of sandalwood (Santalum spicatum) research in Western Australia. Research Bulletin Department of Conservation and Land Management, Western-Australia. No. 4, vii + 53 pp. Piggott MJ et al. 1997. Western Australian sandalwood oil: extraction by different techniques and variations of the major components in different sections of a single tree. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 12(1): 43-46. Raychaudhuri SP and Varma A. 1980. Sandal spike. Review of Plant Pathology. 59 (3): 99-107. Struthers R et al. 1986. Mineral nutrition of sandalwood (Santalum spicatum). Journal of Experimental Botany. 37(182): 1274-1284 Wijesuriya SR and Fox JED. 1985. Growth and nutrient concentration of sandalwood seedlings grown in different potting mixtures. Mulga Research Centre Journal. 8:33-40. LinksNew Crops |

|

Sterculia quadrifida |

|

Peanut Tree |

|

|

Family: |

Sterculiaceae |

General notes:A handsome, compact small tree with the most spectacular seed pod - fire engine red lining with deep black nuts arranged in neat rows. The nut itself is very peanut like and could become a favoured bushfood except for the low yield in each pod and the amount of work to get to the peanut - two separate 'skins' have to be removed before eating. Edible portion:Seed Harvest period:Jun-Aug. Oct -Jan Form:Small, compact tree Yrs to maturity:2-3 Natural Distribution/Growing conditions:Naturally from northern WA and NT in dry or coastal rainforest but does well much further south. Climatic/microclimatic conditions:Tropical-subtropical, perhaps in sheltered temperate locations. Management reference:Unknown Traditional Aboriginal Use:Seed eaten Density:Unknown but 625/ha + judging by its small size Yield at maturity:Low - 6-12 nuts per pod only Harvesting:Hand. The fruits are also relatively easy to harvest as the pods open on the tree. Use shadecloth as ground cloth. Supplied as:Raw Typical value adding:Roasting. It is claimed they pop like popcorn. Current purchasing price:$NCV Perceived demand:Unknown |

|

Tasmannia spp. |

Tas. insipida. Tas. stipitata. Tas. lanceolata |

|

Most particularly T. lanceolata - Mountain Pepper , Snow pepper, Native pepper T. insipida - Pepper bush, Native pepper T. stipitata - Dorrigo pepper. Northern pepper bush |

|

|

Family |

Winteraceae |

General notes:This species was formally known as Drimys lanceolata, Drimys aromatica and Tasmannia aromatica. The hot and spicy leaves of T. lanceolata are found on a large shrub that is endemic to Tasmania and Victoria. Much work is being done on the commercialisation of this species and also on the extraction and use of the oil. T. stipitata is more suited to the drier inland regions - it has much the same culinary qualities as T. lanceolata and is definitely worth pursuing. Edible portion:Leaf and seed Harvest period:Fruits autumn. Leaf year round but Autumn preferred. Yrs to maturity:1-5 Form:Understory shrub to small tree Natural Distribution/Growing conditions:T. lanceolata - grows prolifically in Tas. Also found in Vic and NSW. Stated that it prefers acid loams and sands but tolerates a wide range of soil types. Likes cool, moist, well drained position. This is an understory shrub. T. stipitata - most prevelant along the coast in the Upper Bellingen waterhsed (NSW) but should do well in moderate rainfall regions of other states. Few references to this species. Climatic/microclimatic conditions:T. lanceolata - cool rainforests of Tasmania up to alpine regions. Cool and temperate rainforests of Victoria and NSW. T. stipitata - moderate rainfall regions Management reference:Leaf herbs. Domestic pepper. T. lanceolata requires a cool, damp climate with shade and heavy mulching. Prefers neutral to acid organic rich soil. Male and female plants needed. Responds well to slow release fertiliser. Tolerates severe frosts. Slow growing. Subject to root rot in moist climates and heavy soils. Traditional Aboriginal Use:Unknown Density1200/ha Yield at maturity:Unknown Harvesting:Hand or semi mechanised as for pepper Supplied as:Fresh leaf or berry, dried or dried and ground. Oil. Typical value adding:As for domestic pepper. The leaf develops a subtle, pepper flavour when cooked and the small purple/black berries should make an appropriate substitute to our currently imported pepper. The berries have a hot, peppery zing and can flavour or garnish almost any sauce or even be -baked into a unique pepperbread. Very suited to our game meats to enhance the gaminess. Their unique flavour will even enhance a traditional pepper steak providing that special touch of the bush. Mountain pepperleaf can be used dry or ground and add to hot dishes as a seasoning or used whole like bay leaves. It has a smooth, woody character with a hot zing somewhere between pepper and chilli which reduces with cooking. To enhance the zing, use ground pepperleaf as a seasoning on soups or mains just before serving. Current purchasing price:$15-$70/kg (quoted 1997 - these prices have dropped) Perceived demand:High Research also:Tasmannia insipa (Pepperbush) and Tasmannia stipitata (Dorrigo pepper) From the RIRDC Report

"Cultivation of Native Food Plants in Southeastern Australia"

Although no data has been collected specifically to confirm this, mountain pepper has the

greatest water requirement of all the species being trialled or, conversely, is the least tolerant

of dry soil conditions. It has only survived through the first two years at two of the sites, i.e.

Pt MacDonnell and Kangaroo Is (as well as in the small trial at Mt Gambier). The first

summer (2001-02) was relatively mild and this assisted the survival of mountain pepper at

many of the other sites, eg Jamestown, Moonta, Lyrup, Stawell, and the plants certainly did

grow in the first year, however they did not tolerate the hotter late summer conditions. This

indicates that it may be possible to grow mountain pepper in a wider range of environments. |

|